|

|

The COVID-19 Technology Access Pool: Do Patent Pools Improve Access to Medical Technologies?6/23/2020 On May 29, 2020 the World Health Organization (WHO) officially launched the COVID-19 Technology Access Pool (C-TAP), an initiative which is intended to improve access to existing and new medical technologies, such as therapeutics and vaccines, which are developed in response to the global COVID-19 pandemic.

According to the WHO, the technology pool is meant to ensure better access to existing and new COVID-19 health products through five elements: 1.public disclosure of gene sequences and data; 2.transparent clinical trial publications; 3.funding agreement clauses on availability and trial data publication; 4.promoting the licensing of related technologies to the UN’s Medicines Patent Pool (MPP); and 5.promoting open innovation models and technology transfer. But what exactly are patent pools? And how to they work to improve access to patented treatments? In this post, we will examine patent pools and the advantages and disadvantages that they provide. Patent Pools Another potential mechanism to improve the patent system is to address the hurdle to drug development created by overly broad patents. Overly broad patents are those, for example, which are directed to a drug that targets multiple indications, yet only one of those indications is actually being pursued by the patent holder. By referencing multiple indications in the patent application, the patent holder is blocking others from being able to pursue those indications. Faced with either paying the high costs of licensing or being sued for infringement, many potentially lifesaving technologies may never be developed. The problem presented by overly broad patents can be solved by creating patent pools. A patent pool is an agreement between two or more parties to combine their patents into a single package, or pool. When members of the pool combine their relevant patents together, they can divide the patent rights amongst themselves so that each party takes exclusive or non-exclusive rights to a particular invention covered by the combined patents. Members divide their patent rights along with a promise not to sue one another and without the exchange of licensing fees. This allows each party to the agreement to practice its invention without worrying about the threat of infringement or licensing fees. If the pool includes all relevant patents, the pool can serve as a platform for freedom to operate within that patent landscape. The pool further stimulates innovation by giving its members the opportunity to use technology generated by the industry to bring new products to market and to carry out further reach and development. History of Patent Pools Patent pools have been around for more than a century. One of the original patent pools was created in 1856 for the sewing machine industry. Prior to the creation of the patent pool, sewing machine manufacturers Grover, Baker, Singer, Wheeler, and Wilson were accusing each other of patent infringement. To settle their lawsuits, they all met in Albany, New York. At the meeting, Orlando B. Potter, a lawyer and president of the Grover and Baker Company, proposed that each company pool their patents together instead of spending their money on the infringement suits. Another example of a patent pool was in the early 1990s, when the US government mandated a patent pool for aircraft manufacturing. The need for increased aircraft production arose during the onset of World War I, however, manufacturers of aircraft were faced with threats of infringement and high royalty charges from the relevant patent holders in the area, namely the Wright Brothers and Glenn Curtiss. The government realized that more planes were needed to assist in the war effort and required the creation of a patent pool. This pool ultimate resulted in the formation of the Manufacturers Aircraft Association. While patent pools have long been established in other technological areas, patent pools within the pharmaceutical industry are relatively new. In 2008, the World Health Organization (WHO) recognized the important role that patent pools may play in increasing access to drugs. As a result, attempts to establish a patent pool for severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and for neglected tropical diseases have been made. In July 2010, the Medicines Patent Pool was established to foster the development of HIV/AIDS drugs. The Medicines Patent Pool solicits voluntary licenses from patent owners of antiretroviral medicines to create a pooled resource. This pooled resource can then be accessed by drug manufacturers to develop new and adapted formulations of drug products, such as heat-stable products, lower-dose formulations, pediatric medicines and fixed-dose combinations, that will be sold in developing countries. Advantages of a Patent Pool A patent pool may be beneficial for all the parties involved, including the drug manufacturers, the patent holders, and the people receiving the treatment. For drug manufacturers, for instance, a patent pool eliminates the uncertainty and expense of negotiating licenses where several different patent holders may hold rights to a single drug or treatment. It also encourages further research by lowering the cost associated with licensing technology to create new medicines. For patent holders, on the other hand, the patent pool offers the opportunity to enjoy royalty streams from different sources and provides a collaborative platform for enhancing access in developing countries. Since the drugs that are developed as a result of the pool are limited to developing countries, the pool would not affect the patent holders’ rights in higher-income markets. Accordingly, patent holders would be able to continue selling the rights to their drugs and treatment at higher prices in developed markets. For people living with HIV/AIDS, most importantly, the patent pool would make medicine more affordable. It is estimated that the Medicines Patent Pool could impact an estimated 33.3 million people living with HIV/AIDS. Patent pools offer several other advantages for members of the pool. First, they can help overcome blocking patents. If all the relevant patents are combined in the pool, then there are no outstanding patents that can act to block the use of those patents. Second, patent pools can reduce the overall transaction costs associated with the patents by lowering licensing fees and reducing patent infringement suits. They do so by allowing licensees to negotiate with only one party, eliminating the need for potential licensees to conduct their own patent landscape analysis, and eliminating problems associated with royalty stacking. Since patent pools allow members of the pool to use the technology without being sued for patent infringement, patent pools can reduce and even eliminate patent litigation settlements. Third, patent pools allow intellectual property other than patents to be included in the pool. This is especially important because it allows the inclusion of trade secrets that may be important to the research and development behind the products. Finally, patent pools further allow members of the pools to share in the risk of developing the technology. By spreading the risk across all members of the pool, no one company is solely responsible for putting in all the time, effort and money in developing a product. Disadvantages of a Patent Pool While there are definite advantages to patent pools, there are also several disadvantages to them. One of these disadvantages is the uncertain return on investment that can be generated. Pharmaceutical products are costly to develop, and when companies invest a significant amount of time and money into developing technology that ultimately becomes part of the patent pool, they expect a return on their investment. However, that return will have to be shared amongst the other members of the pool. Determining exactly how the member companies divide the return will be complicated and may depend on a variety of factors, such as a company’s contribution to the initial technology and to the final product, will need to be considered. Second, patent pools may actually shield invalid patents from being invalidated in court. By protecting invalid patents, patent pools may require that royalties are paid on a technology that would be part of the public domain if the patents were actually litigated in court. This concern could be alleviated if all candidate patents to the pool are reviewed and examined by an impartial expert to determine their validity. Finally, patent pools may create some antitrust issues by eliminating competition through collusion and price fixing. Companies that are not members of the pool may be at a competitive disadvantage since they will not be able to obtain the necessary licenses to develop a product. Since companies will not have access to the necessary technology, these companies may struggle to prosper. Patent pools strive to solve the problem of balancing innovation of new drugs and access for all. Companies that are members of the pool would, in theory, benefit because they could develop new therapies.

0 Comments

Chimeric antigen receptor, or CAR, T cell therapies use the body’s own T cells to fight off cancers. The development of such cellular immunotherapies is becoming increasingly popular technology for treating cancer. Novartis’ Kymriah and Kite’s Yescarta are currently the only two FDA approved therapies on the market but many other companies are looking to launch products in this highly lucrative and therapeutically promising field.

Despite the promising nature of cellular therapeutics, however, CAR T cell therapeutics present some unique IP challenges that should be resolved early on in the development process in order to minimize hurdles when it comes to commercialization. Here we discuss some of these unique challenges specifically when it comes to seeking a freedom to operate, of FTO. 1. Highly crowded landscape. The patent landscape for cellular immunotherapies is highly crowded with many actors already established in the space. CARs involve several different components. The current generation of CARs involve a binding domain, a transmembrane domain, a signaling domain, and at least one co-stimulatory domain. Companies already have their own proprietary CARs with modifications to any of these domains. The two FDA approved products are both directed to CD19, for instance, and many other groups are working on CD19 as well. 2. Multiple components. Since CAR T cell therapies involve multiple components, each of which will require its own separate FTO. As mentioned above, CARs involve a binding domain, a transmembrane domain, a signaling domain, and one or more co-stimulatory domains. To effectively launch a product without infringing a third party’s patent, each element of the CAR must have a clear FTO. Even one third party patent with claims covering any one of the CAR elements could subject the company to infringement litigation. 3. Method patents. Methods of manufacturing CAR T cell therapies should not be overlooked. While composition claims are often the most favored, there is significant value to patenting methods related to engineering the CAR T cells, or culturing and expanding them. Companies that develop CAR T cells may run afoul of the method claims even though the composition of the CAR T cell itself is different. Therefore, it is not only important to analyze patents directed to each of the components, but also to any methods that can be used to manufacture the cells. 4. Global nature. CAR T cell therapies, by their very nature, may require certain steps of the process to be carried out in different countries. For instance, the current generation of CAR T cells use autologous cells, meaning that the cells that are used and modified are those taken directly from the patient. Once they are taken from the patient, they can be transported to a lab in a different location, even a different country, for modification. The extraction, modification, and subsequent re-administration can thus happen in different jurisdictions. An FTO, therefore, should not only be limited to the country in which the therapy is going to be commercialized, but also in the countries in which individual steps of the process will be carried out. Due to their complex nature, CAR T cell therapies present unique obstacles to commercialization. Companies developing products in this space need to be aware of these challenges early on in the development process so that they can take the proper actions (e.g., seek licenses, design around existing patents, challenge existing patents, etc.) to minimize their risk of commercialization. Strong patents are the foundation of any valuable patent portfolio. In my latest book, Billion Dollar Patents, I explore ways to draft patents and build strong patent that will not only provide products with a competitive edge but that will also be upheld should they be challenged in a post-grant proceeding.

Drafting strong patents is equally important in today’s pandemic climate. We have seen many companies and universities devote significant resources to COVID-19 research in hopes of developing a vaccine or cure for the disease. With so many companies working to develop a cure, companies are rushing to patent their innovations. Despite this rush to the patent office, it is important to still follow best practices when filing applications. Below are five strategies when it comes to filing COVID-19 related inventions. 1. File quickly The U.S. and other countries have a first-to-file patent system. Accordingly, it is important to file patent applications quickly before your competitor does. If you file an application even a day after a competitor does, you likely lose all rights to that invention. Despite the rush to file, it is important to understand that the pandemic does not suspend patent laws. Accordingly, patent applications must still satisfy the various requirements of patent law, especially written description and enablement, in order to have a defendable priority date. This means that to actually benefit from the filing date of the application and predate competitors, that patent application will need to have sufficient information and data to support the claims. Generally speaking, the more information and the more data you provide in an application, the better chances you will have to end up with strong claims. Problems may arise, however, when you do not have enough data because experiments are still in progress. In these situations, it is still important to file patent applications early using hypothetical examples. While hypothetical examples are viewed differently across jurisdictions, they may provide a viable alternative when experimental data is not available. 2. File Often Not only is it important to file early, it is also important to file often. This is particularly true when experimental data is not immediately available as discussed above. It is important to remember that you are not limited to filing just one provisional patent application. You can file as many as you want during the course of the year and then merge them together to file one utility or non-provisional application. In these situations, you could file new provisional applications as soon as new data becomes available. One caveat to be aware of is that the new data will only provide priority to the date on which it was filed. Unless it was supported by adequate disclosure, such as a hypothetical example, it will likely not benefit from any earlier provisional filing dates. This makes it even more important to file updated provisional applications as often as possible. In addition to covering new data, the patent applications should cover work arounds and foreseeable new developments to the invention. Patents provide a value in create barriers to market entry and “excluding” others from your field. By filing applications to modifications, you can expand your footprint in the market. 3. Take advantage of USPTO’s accelerated program The USPTO is currently offering an accelerated program for COVID-19 related technologies, called the COVID-19 Prioritized Examination Pilot Program (May 14, 2020). It is applicable to any product or process related to COVID-19 that requires FDA approval such as INDs, IDEs, NDAs, BLAs, PMAs, and EUAs. To submit a patent application under this program, that patent application must be limited to 4 independent claims or 30 claims in total. Only small or micro entities can apply for this accelerated pathway and only 500 cases will be permitted in total. As part of the program, the USPTO hopes to reach final deposition with 1 year and possibly within 6 months. By taking advantage of the USPTO’s accelerated program, companies can expedite the process by which they can obtain patent protection for their products. 4. Conduct quick FTO studies As previously mentioned, the coronavirus pandemic does not suspend patent laws. Companies therefore still need to be aware of potentially blocking third party patents that may present hurdles to commercialization. Such patents can be identified with a freedom to operate (FTO) study. This is particularly true when companies are using pre-existing drugs, such as Gileads’ antiviral, Remdesivir. Even when the process is rushed, conducting FTO studies during the course of development is important to identifying potential roadblocks to commercialization. This allows companies to proactively seek licenses or workarounds to their inventions. 5. Prepare for compulsory licensing situations We are in uncharted territories. While only a handful of countries have ever issued a compulsory license, which would allow a country to circumvent a patent to manufacture and distribute a patent protected drug to its public, companies need to prepare for the possibility that this could happen. Earlier in March, Israel issued a compulsory license to AbbVie’s HIV treatment Kaletra® for use to treat COVID-19. It is likely that more countries will employ similar measures depending on what drug will prove effective to treat the disease. To put themselves in the best possible situation, companies need to proactively think about how compulsory licensing could be used for their products and better prepare themselves for dealing with that possibility. While the need to find a treatment or a cure for COVID-19 has created a rush to patent coronavirus technologies, companies in this space should be mindful of following existing patent laws as well as being aware of the new opportunities afforded to them. Whether it’s the current pandemic or simply a change in business needs, there are many reasons why a signed agreement may no longer serve the interests of a party. So, what can a company do when it finds that it is party to an agreement that no longer serves its interests? The answer is simple – it can renegotiate the agreement.

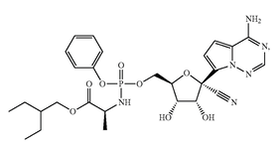

This answer may surprise many because people generally think that once an agreement is signed, it is final. In fact, renegotiating agreements is definitely possible, and it is a strategy I have successfully used on multiple occasions. This strategy should, however, be used with caution. Time should be taken to properly negotiate agreements upfront to avoid the hassle of having to renegotiate later. Nevertheless, there are situations requiring agreements to be renegotiated. Excessive financial burden One reason for renegotiating an agreement is when one party is unable to meet the financial costs of an agreement. License agreements are one example where this can come up, but they are certainly not the only ones. Since license agreements often call for a number of different payments—including annual maintenance payments, reimbursement of patent prosecution expenses, milestone payments, and royalty payments—financial obligations on licensees can be immense. Luckily, with so many different possible areas for payment, restructuring payments such that they are more on the backend is often enough to help a cash-strapped licensee. Change in business needs Another reason for renegotiating an agreement is when one party is unwilling to meet the financial costs of an agreement, given its current needs and plans. In this scenario, the party is able to pay, but it might not make business sense to do so. For instance, I worked on another license agreement in which the licensee changed directions in its development plan, and the licensed product was no longer the primary focus of the company. To the licensee, the license was a “nice to have” rather than a “must have.” Since having the license continue was more favorable than terminating it, the licensor was able and willing to agree to lesser financial terms. By renegotiating the financial terms, the licensor was able to keep its financial stream alive, and the licensee was able to reduce its business expenses. Unable to meet milestones Another reason to renegotiate agreements is when parties are unable to meet agreed-upon milestones. This situation occurs in a variety of agreements, including license, research collaboration, and clinical trial agreements. What generally happens is that one party cannot meet the milestones set out in the agreement, and the parties must come together to revise the original agreement, assuming they want to keep it alive. For example, in a license agreement, the development of a licensed product might have moved slower than expected, so the parties can agree to delay initiation of a phase I clinical trial and any associated milestone payments beyond the originally agreed upon date. By renegotiating milestones, associated timelines, and costs, both parties can maintain an agreement without running afoul of its terms. Poorly drafted original agreement A final reason for renegotiating is when the original agreement is poorly drafted, which may create unnecessary confusion about a party’s obligations, place unintended obligations and/or liabilities on a party, or generate additional burdens for a party. To illustrate this last point, I was involved in renegotiating a license agreement in which royalty payments to the licensor were not based on revenue generated by a licensed product but on revenue generated by the entire company. This meant the licensor would benefit from its licensed product as well as all of the products and services sold by the licensee company. As written, this agreement was unfair and likely not what was ever intended by the parties. Nevertheless, such language made it into the final executed version and was something with which we had to deal and amend. Assuming both parties want to continue working toward the objective of the original agreement, renegotiating is an effective way to keep a relationship going while making its terms acceptable to both parties. When faced with the possibility of one party walking away and terminating an agreement, it is often in the interest of both parties to come together to find mutually agreed upon terms under which both are willing to continue. Wuhan Institute of Virology filed a patent application at the Chinese patent office on the use of Gilead’s Remdesivir for treating COVID-19 on January 21, 2020. The patent application raises questions of how could Wuhan file a patent application to something (in this case, a drug) that does not belong to them. Many people have a difficult time understanding how a third-party can patent something using a product belonging to someone else. To understand why this is the case, you must first understand that a patent is a negative right -- it is not a positive right. As such, a patent does not allow the owner to make, use, offer to sell, or sell the invention. A patent merely allows the owner to prevent others from doing the same. There may be other patents or regulatory hurdles blocking the patent owner from actually making or using his own product. In other words, just because you get a patent, does not mean that you can actually commercialize your product. There is a difference between patenting a product and having freedom to operate (FTO) to use that product. I’ve discussed the differences between patentability and FTO in previous posts, but here I will discuss it using Wuhan’s patent application to using Remdesivir for treating COVID-19 as an example. Gildead’s Patents for Remdesivir Gilead has several patents covering its antiviral drug, Remdesivir. For the purposes of this post, I will only examine two. Gilead filed U.S. patent application number 14/613,719 on February 4, 2015 which claimed priority to U.S. Provisional Patent Application Number 61/366,609 filed on July 22, 2010. This application issued on September 4, 2018 as U.S. Patent Number 10,065,958 (the ‘958 patent) with independent claim 1 broadly directed to the composition as follows: 1.A compound that is Gilead also filed U.S. patent application 16/265,016 (the ‘016 patent application) on February 1, 2019 which claims priority to U.S. Provisional Patent Application Number 62/219,302, filed on September 16, 2015, and U.S. Provisional Patent Application Number 62/239,696, filed on October 9, 2015. This application was allowed on February 6, 2020, with claims specifically directed to a method for treating a coronavirus infection in a human with Remdesivir.

Patentability of Wuhan’s Patent Application for COVID-19 The patentability of Wuhan’s patent application for COVID-19 will turn on whether the application satisfies the requirements of patentability in the country that it is seeking the patent. These include i) novelty, ii) inventive step/obviousness, and iii) written description and enablement. The patent application has a good chance of satisfying the novelty requirement since COVID-19 is a novel coronavirus and Gilead’s patents do not specifically mention COVID-19. Likewise, written description will likely be satisfied assuming the patent application was filed with the necessary data and descriptions. The main hurdle to patentability will be inventiveness, or obviousness. Since Gilead’s patent specifically mentions using Remdesivir to treat viral infections caused by a Coronaviridae virus, the patent office could reject the claims because, arguably, it could have been obvious to one skilled in the art to use Remdesivir for any coronavirus, including COVID-19. To overcome this rejection, Wuhan will need to show that there is something unique or unexpected in its treatment methods, whether it is the dose, the dosing regimen, or even the safety profile. Overall, obtaining a patent will not be automatic for Wuhan but it is certainly possible that they will receive a patent with claims narrowly tailored to treating COVID-19. Freedom to Operate (FTO) Assuming Wuhan is able to receive a patent, the next question is whether it will be able to market or sell the treatment. This comes down to whether or not Wuhan has freedom to operate, or FTO. As the name implies, this analysis requires determining whether there are any blocking patents in the geographic region in which you plan to commercialize (i.e., make, sell, distribute, use, and otherwise market) the indicated therapy. That is, in order to determine whether or not Wuhan can commercialize the COVID-19 therapy, you have to see whether that therapy falls within the scope of any third-party patent rights within the jurisdiction of interest. In this case, the potential blocking IP would be Gilead’s patent for Remdesivir. Looking at the U.S. claims, Gilead’s ‘958 patent broadly claims the composition. It is not limited by any additional features. As such, the ‘958 patent gives Gilead rights to Remdesivir for all uses. Since Wuhan’s patent application relies on Remdesivir, it’s therapy would fall within the scope of the ‘958 patent. Moreover, Wuhan’s therapy would likely also run afoul of Gilead’s ‘016 patent application which is directed to the method of treating coronaviridae infection with Remdesivir. Since COVID-19 is a specific coronavirus, any methods of “treating COVID-19” would likely fall within the scope of “treating coronaviridae infection.” Just as with the ‘958 patent, Wuhan’s application of using Remdesivir to treat COVID-19 infections would encounter obstacles with the ‘016 patent application. Conclusion As you can see, the questions of how Wuhan can patent a treatment for COVID-19 using Gilead’s pre-existing technology involves understanding the differences between being able to patent an invention and being able to actually commercialize it. Of course, finding that certain patent rights exist that could block commercialization of Remdisivir for the treatment of COVID-19 does not necessarily end the analysis. Designing around Gilead’s patents, licensing Gilead’s patents, or even obtaining a compulsory license in this situation can help Wuhan overcome the patent hurdles to commercialization. |

Welcome!BioPharma Law Blog posts updates and analyses on IP topics, FDA regulatory issues, emerging legal developments, and other news in the constantly evolving world of biotech, pharma, and medical devices. Archives

March 2021

Categories

All

|

Practices |

Company

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed