|

|

|

Strong patents are the foundation of any valuable patent portfolio. In my latest book, Billion Dollar Patents, I explore ways to draft patents and build strong patent that will not only provide products with a competitive edge but that will also be upheld should they be challenged in a post-grant proceeding.

Drafting strong patents is equally important in today’s pandemic climate. We have seen many companies and universities devote significant resources to COVID-19 research in hopes of developing a vaccine or cure for the disease. With so many companies working to develop a cure, companies are rushing to patent their innovations. Despite this rush to the patent office, it is important to still follow best practices when filing applications. Below are five strategies when it comes to filing COVID-19 related inventions. 1. File quickly The U.S. and other countries have a first-to-file patent system. Accordingly, it is important to file patent applications quickly before your competitor does. If you file an application even a day after a competitor does, you likely lose all rights to that invention. Despite the rush to file, it is important to understand that the pandemic does not suspend patent laws. Accordingly, patent applications must still satisfy the various requirements of patent law, especially written description and enablement, in order to have a defendable priority date. This means that to actually benefit from the filing date of the application and predate competitors, that patent application will need to have sufficient information and data to support the claims. Generally speaking, the more information and the more data you provide in an application, the better chances you will have to end up with strong claims. Problems may arise, however, when you do not have enough data because experiments are still in progress. In these situations, it is still important to file patent applications early using hypothetical examples. While hypothetical examples are viewed differently across jurisdictions, they may provide a viable alternative when experimental data is not available. 2. File Often Not only is it important to file early, it is also important to file often. This is particularly true when experimental data is not immediately available as discussed above. It is important to remember that you are not limited to filing just one provisional patent application. You can file as many as you want during the course of the year and then merge them together to file one utility or non-provisional application. In these situations, you could file new provisional applications as soon as new data becomes available. One caveat to be aware of is that the new data will only provide priority to the date on which it was filed. Unless it was supported by adequate disclosure, such as a hypothetical example, it will likely not benefit from any earlier provisional filing dates. This makes it even more important to file updated provisional applications as often as possible. In addition to covering new data, the patent applications should cover work arounds and foreseeable new developments to the invention. Patents provide a value in create barriers to market entry and “excluding” others from your field. By filing applications to modifications, you can expand your footprint in the market. 3. Take advantage of USPTO’s accelerated program The USPTO is currently offering an accelerated program for COVID-19 related technologies, called the COVID-19 Prioritized Examination Pilot Program (May 14, 2020). It is applicable to any product or process related to COVID-19 that requires FDA approval such as INDs, IDEs, NDAs, BLAs, PMAs, and EUAs. To submit a patent application under this program, that patent application must be limited to 4 independent claims or 30 claims in total. Only small or micro entities can apply for this accelerated pathway and only 500 cases will be permitted in total. As part of the program, the USPTO hopes to reach final deposition with 1 year and possibly within 6 months. By taking advantage of the USPTO’s accelerated program, companies can expedite the process by which they can obtain patent protection for their products. 4. Conduct quick FTO studies As previously mentioned, the coronavirus pandemic does not suspend patent laws. Companies therefore still need to be aware of potentially blocking third party patents that may present hurdles to commercialization. Such patents can be identified with a freedom to operate (FTO) study. This is particularly true when companies are using pre-existing drugs, such as Gileads’ antiviral, Remdesivir. Even when the process is rushed, conducting FTO studies during the course of development is important to identifying potential roadblocks to commercialization. This allows companies to proactively seek licenses or workarounds to their inventions. 5. Prepare for compulsory licensing situations We are in uncharted territories. While only a handful of countries have ever issued a compulsory license, which would allow a country to circumvent a patent to manufacture and distribute a patent protected drug to its public, companies need to prepare for the possibility that this could happen. Earlier in March, Israel issued a compulsory license to AbbVie’s HIV treatment Kaletra® for use to treat COVID-19. It is likely that more countries will employ similar measures depending on what drug will prove effective to treat the disease. To put themselves in the best possible situation, companies need to proactively think about how compulsory licensing could be used for their products and better prepare themselves for dealing with that possibility. While the need to find a treatment or a cure for COVID-19 has created a rush to patent coronavirus technologies, companies in this space should be mindful of following existing patent laws as well as being aware of the new opportunities afforded to them.

0 Comments

Whether it’s the current pandemic or simply a change in business needs, there are many reasons why a signed agreement may no longer serve the interests of a party. So, what can a company do when it finds that it is party to an agreement that no longer serves its interests? The answer is simple – it can renegotiate the agreement.

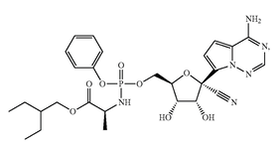

This answer may surprise many because people generally think that once an agreement is signed, it is final. In fact, renegotiating agreements is definitely possible, and it is a strategy I have successfully used on multiple occasions. This strategy should, however, be used with caution. Time should be taken to properly negotiate agreements upfront to avoid the hassle of having to renegotiate later. Nevertheless, there are situations requiring agreements to be renegotiated. Excessive financial burden One reason for renegotiating an agreement is when one party is unable to meet the financial costs of an agreement. License agreements are one example where this can come up, but they are certainly not the only ones. Since license agreements often call for a number of different payments—including annual maintenance payments, reimbursement of patent prosecution expenses, milestone payments, and royalty payments—financial obligations on licensees can be immense. Luckily, with so many different possible areas for payment, restructuring payments such that they are more on the backend is often enough to help a cash-strapped licensee. Change in business needs Another reason for renegotiating an agreement is when one party is unwilling to meet the financial costs of an agreement, given its current needs and plans. In this scenario, the party is able to pay, but it might not make business sense to do so. For instance, I worked on another license agreement in which the licensee changed directions in its development plan, and the licensed product was no longer the primary focus of the company. To the licensee, the license was a “nice to have” rather than a “must have.” Since having the license continue was more favorable than terminating it, the licensor was able and willing to agree to lesser financial terms. By renegotiating the financial terms, the licensor was able to keep its financial stream alive, and the licensee was able to reduce its business expenses. Unable to meet milestones Another reason to renegotiate agreements is when parties are unable to meet agreed-upon milestones. This situation occurs in a variety of agreements, including license, research collaboration, and clinical trial agreements. What generally happens is that one party cannot meet the milestones set out in the agreement, and the parties must come together to revise the original agreement, assuming they want to keep it alive. For example, in a license agreement, the development of a licensed product might have moved slower than expected, so the parties can agree to delay initiation of a phase I clinical trial and any associated milestone payments beyond the originally agreed upon date. By renegotiating milestones, associated timelines, and costs, both parties can maintain an agreement without running afoul of its terms. Poorly drafted original agreement A final reason for renegotiating is when the original agreement is poorly drafted, which may create unnecessary confusion about a party’s obligations, place unintended obligations and/or liabilities on a party, or generate additional burdens for a party. To illustrate this last point, I was involved in renegotiating a license agreement in which royalty payments to the licensor were not based on revenue generated by a licensed product but on revenue generated by the entire company. This meant the licensor would benefit from its licensed product as well as all of the products and services sold by the licensee company. As written, this agreement was unfair and likely not what was ever intended by the parties. Nevertheless, such language made it into the final executed version and was something with which we had to deal and amend. Assuming both parties want to continue working toward the objective of the original agreement, renegotiating is an effective way to keep a relationship going while making its terms acceptable to both parties. When faced with the possibility of one party walking away and terminating an agreement, it is often in the interest of both parties to come together to find mutually agreed upon terms under which both are willing to continue. Wuhan Institute of Virology filed a patent application at the Chinese patent office on the use of Gilead’s Remdesivir for treating COVID-19 on January 21, 2020. The patent application raises questions of how could Wuhan file a patent application to something (in this case, a drug) that does not belong to them. Many people have a difficult time understanding how a third-party can patent something using a product belonging to someone else. To understand why this is the case, you must first understand that a patent is a negative right -- it is not a positive right. As such, a patent does not allow the owner to make, use, offer to sell, or sell the invention. A patent merely allows the owner to prevent others from doing the same. There may be other patents or regulatory hurdles blocking the patent owner from actually making or using his own product. In other words, just because you get a patent, does not mean that you can actually commercialize your product. There is a difference between patenting a product and having freedom to operate (FTO) to use that product. I’ve discussed the differences between patentability and FTO in previous posts, but here I will discuss it using Wuhan’s patent application to using Remdesivir for treating COVID-19 as an example. Gildead’s Patents for Remdesivir Gilead has several patents covering its antiviral drug, Remdesivir. For the purposes of this post, I will only examine two. Gilead filed U.S. patent application number 14/613,719 on February 4, 2015 which claimed priority to U.S. Provisional Patent Application Number 61/366,609 filed on July 22, 2010. This application issued on September 4, 2018 as U.S. Patent Number 10,065,958 (the ‘958 patent) with independent claim 1 broadly directed to the composition as follows: 1.A compound that is Gilead also filed U.S. patent application 16/265,016 (the ‘016 patent application) on February 1, 2019 which claims priority to U.S. Provisional Patent Application Number 62/219,302, filed on September 16, 2015, and U.S. Provisional Patent Application Number 62/239,696, filed on October 9, 2015. This application was allowed on February 6, 2020, with claims specifically directed to a method for treating a coronavirus infection in a human with Remdesivir.

Patentability of Wuhan’s Patent Application for COVID-19 The patentability of Wuhan’s patent application for COVID-19 will turn on whether the application satisfies the requirements of patentability in the country that it is seeking the patent. These include i) novelty, ii) inventive step/obviousness, and iii) written description and enablement. The patent application has a good chance of satisfying the novelty requirement since COVID-19 is a novel coronavirus and Gilead’s patents do not specifically mention COVID-19. Likewise, written description will likely be satisfied assuming the patent application was filed with the necessary data and descriptions. The main hurdle to patentability will be inventiveness, or obviousness. Since Gilead’s patent specifically mentions using Remdesivir to treat viral infections caused by a Coronaviridae virus, the patent office could reject the claims because, arguably, it could have been obvious to one skilled in the art to use Remdesivir for any coronavirus, including COVID-19. To overcome this rejection, Wuhan will need to show that there is something unique or unexpected in its treatment methods, whether it is the dose, the dosing regimen, or even the safety profile. Overall, obtaining a patent will not be automatic for Wuhan but it is certainly possible that they will receive a patent with claims narrowly tailored to treating COVID-19. Freedom to Operate (FTO) Assuming Wuhan is able to receive a patent, the next question is whether it will be able to market or sell the treatment. This comes down to whether or not Wuhan has freedom to operate, or FTO. As the name implies, this analysis requires determining whether there are any blocking patents in the geographic region in which you plan to commercialize (i.e., make, sell, distribute, use, and otherwise market) the indicated therapy. That is, in order to determine whether or not Wuhan can commercialize the COVID-19 therapy, you have to see whether that therapy falls within the scope of any third-party patent rights within the jurisdiction of interest. In this case, the potential blocking IP would be Gilead’s patent for Remdesivir. Looking at the U.S. claims, Gilead’s ‘958 patent broadly claims the composition. It is not limited by any additional features. As such, the ‘958 patent gives Gilead rights to Remdesivir for all uses. Since Wuhan’s patent application relies on Remdesivir, it’s therapy would fall within the scope of the ‘958 patent. Moreover, Wuhan’s therapy would likely also run afoul of Gilead’s ‘016 patent application which is directed to the method of treating coronaviridae infection with Remdesivir. Since COVID-19 is a specific coronavirus, any methods of “treating COVID-19” would likely fall within the scope of “treating coronaviridae infection.” Just as with the ‘958 patent, Wuhan’s application of using Remdesivir to treat COVID-19 infections would encounter obstacles with the ‘016 patent application. Conclusion As you can see, the questions of how Wuhan can patent a treatment for COVID-19 using Gilead’s pre-existing technology involves understanding the differences between being able to patent an invention and being able to actually commercialize it. Of course, finding that certain patent rights exist that could block commercialization of Remdisivir for the treatment of COVID-19 does not necessarily end the analysis. Designing around Gilead’s patents, licensing Gilead’s patents, or even obtaining a compulsory license in this situation can help Wuhan overcome the patent hurdles to commercialization. Patent landscape studies are really powerful tools. They can provide a lot of valuable information to a company about competitor’s strategies, currently existing and unexploited market opportunities, and technology trends, and can even increase the valuation of a company and its patent portfolio. We discussed some of this information in a previous post.

But did you know that investors also place a large value on landscape studies? Below are five reasons why investors like to see landscape studies when evaluating a company. 1. Landscape studies provide an overall picture of a company’s market position in the context of its own field and provide a glimpse into potential pathways for future growth. Such studies have powerful mapping capabilities that will not only show you where your company currently stands in the market, but will also identify white space that can offer additional opportunities for growth and development. Taking advantage of this information can help a company plan its current and further research projects. 2. Landscape studies can identify hurdles to commercialization. One such hurdle can come from market over-saturation. If a company is developing IP and products in a crowded space, that company may not only face a lot of competition when it enters the market, but may also face potential infringement claims. Another hurdle can be from technology limitations. If a company is developing IP in a space that has no active competition, there may either not be demand for the product or there may be serious technical problems with the underlying technology. Identifying such issues is important when evaluating a company’s potential market strength. 3. Landscape studies provide important information about potential competitors. Not all competitors are equal. A landscape study will not only identify competitors in a company’s space, but it can also uncover the relevant strengths of those competitors. Some competitors may have already launched products while others may have only just filed patent applications. Knowing this information can help a company analyze the relative threats that those competitors present and can also provide valuable insights should your company choose to negotiate a license or collaboration agreement with those competitors. 4. Landscape studies can also identify trends in the technology. When mapping the marketplace, these studies can reveal how technology has evolved in a specific space. In the CAR T cell therapy space, for instance, there are currently at least four generations of technology that are being pursued. If a company is working on the first-generation version, that company may be missing out on important market advancements and opportunities that are available to those who are pursuing fourth-generation technology. 5. Landscape studies can breathe life into a company’s business strategy. While this seems like a no-brainer, it is amazing to see companies have no plan or reasoning to justify why they are pursuing certain compounds, certain indications, or certain platform technologies. When done correctly, landscape studies can be used to quantitatively evaluate and justify a company’s rationale for devoting resources to the pursuit of certain development projects while abandoning others. Overall, landscape studies can be incredibly valuable tools that support and guide a company’s business strategy. Having one on hand, and keeping it updated, when pitching to investors can improve your chances of being seen, respected, and appreciated. If you have any questions about performing landscape analyses or updating a landscape analysis, please feel free to reach out to us. We are often asked by inventors if their ideas and creations belong to their employers. We see this particularly with researchers who develop something at home, in the evening, or on weekends. With most people working from home due to the ongoing coronavirus pandemic, many people have some free time and think that now the right time develop a new app or even write a book.

With creating new inventions, however, there is a risk that your employer could claim ownership over your intellectual property. This is because your employer generally owns the IP rights you created during the scope of your employment. However, you can retain your IP rights as long as your IP is developed outside the scope of your employment. Scope of employmentSo what does “scope of employment” mean and what falls under the “scope of your employment?” Scope of employment really comes down to your employment agreement and refers to the work and duties you were hired to perform. If you were hired by a biotech company to research and develop new gene therapies, then any gene therapies you develop would probably fall under the scope of your employment. However, if you develop a language learning program, that program would likely fall outside the scope of your employment. More challenging situations arise when the IP you develop is similar to that which you were hired to develop. In these situations, your employment agreement will be instrumental in outlining exactly what duties you were hired to perform. However, even the employment agreement can sometimes be unclear when it comes to outlining your duties. To minimize the likelihood that your employer can claim rights to your invention, the following four tips can help demonstrate that your IP was developed outside the scope of your employment. 1. Start recording everything - Maintaining meticulous records helps reduce questions surrounding ownership over the new IP and can help prove your ownership. Write down your project dates, including the start date, in a diary and keep track of its development stages, including any discussions with third parties that you have had. You can also maintain an electronic record by sending an email to your personal address that documents your contributions. 2. Use your time wisely - Make sure you work on your project outside of your work hours. This means focusing on your project only in the evenings and weekends if your work hours are from nine to five. If you work on your project during work hours, you can risk the employer claiming rights to it. 3. Use separate devices – Similar to the point above, make sure you work on your project using your own devices. Do not use your employer’s computers, tools, copiers, scanners, or other devices for your personal work. Use only your own personal computer or laptop. This means that any inspiration you get while working should be written on paper and pen, and not on your office device. Likewise, use only your personal email when communicating about your invention. 4. Use your own money – Finally, make sure you fund your project using your own resources. This means using your own money to pay for expenses like electricity, paper, permits, and raw materials. Do not claim money from your company for any IP-related expenses. If you use your employer’s money to pay for any parts of your invention, you risk jeopardizing ownership of it. At the end of the day, whether your employer can claim rights to your invention will come down to whether or not the invention was created within the “scope of your employment.” By using your own resources, time, and money, and keeping a detailed journal of your developments, you can increase the likelihood that your invention will stay in your hands. On Monday, April 27, 2020, the USPTO published a decision that claims that a machine cannot be an inventor for the purposes of obtaining patent protection. Rather, an inventor must be human or “natural person.”

This decision reminded me of a discussion I had earlier this year when I participated on a conference panel in Dubai to explore patent issues in the new and exciting field of AI. My focus specifically was AI as it applies to biotechnologies, pharmaceutical technologies, and medical devices. While the prospect for developing AI-based technologies seems promising, obtaining valuable patent protection on such technologies can be challenging. Here I will examine some of the challenges presented in patenting AI in the life sciences field as well as discuss five strategies that may improve the chances for patenting these new technologies. Challenges AI can have many applications ranging from voice-powered personal assistants like Siri and Alexa to trying to identify ones of the most infamous serial kills of all time, the Zodiac Killer. Within the life sciences field, AI has so far been used to detect cancer in radiology, improve accuracy of CRISPR technology by predicting and preventing CRISPR from accidentally editing genomic regions similar to target region, generate and validate new drug compounds, and even to calculate the impact of various treatments on brain tumors by analyzing MRIs. Because of its unique nature, AI-based technologies in life sciences face problems from both the AI side as well as the life sciences side. From the AI side, Section 101 patent eligibility issues, namely Alice, and Section 112 written description present major hurdles. In addition, there are questions stemming from DDR and Enfish about patenting software. From the life sciences side, Section 101 patent eligibility, namely from Myriad, Section 112 written description, and issues related to inherently, obviousness, and double patenting all present hurdles. Navigating these hurdles individually can be challenging by itself but navigating multiple at the same time can be even more so. Moreover, the past several years have see uncertainties in court decisions and USPTO guidances and thus the eligibility criteria for AI-based technologies is unclear. This uncertainty stems from the Mayo and Alice cases. So what do you do when you try to patent a technology with so many uncertainties? Below are five strategies that can help First, narrow the claims to a specific product. This is not the time to try to carve as much white space for yourself as possible. Focus on the product and make sure the claims cover that product. As the law develops around AI, broadening the scope of such claims will likely be possible but until then, patent eligibility and written description are hurdles that, more often than not, will demand a more tailored approach to claim drafting. Second, while you want to narrow your claim to cover your particular product, do not just rely on one claim to do so. Instead, draft multiple claims with different claim scopes. This will give you the best chance of not only getting a claim allowed, but also potentially allowing some claims to withstand a post-grant challenge should one arise. In my book, Billion Dollar Patents, I discuss the importance of having varying claim scopes as a way to increase the likelihood that some variations could withstand challenges even when others may not. Third, draft the specification to include as much detail as possible about the invention, specifically about its novel and nonobvious features. During prosecution of the application, you may need to rely on these features to amend the claims and include limitations. Since these types of inventions, by their nature, present written description challenges, the more information you provide about its features, the better the chances to overcome Section 112 hurdles. Fourth, draft the specification to show how the invention provides a solution to a problem. This is a follow up to the previous point about providing as much detail as possible about the invention. If you can show that the invention solves a problem, the invention becomes more concrete because it has a purpose. In addition, the 2018 European patent eligibility guidelines require that the applicant “establish a causal link to the technical purpose,” so following the guidelines from a country that is more evolved in its eligibility guidelines can be helpful. Finally, choose the jurisdictions in which you want to patent in carefully. You may want to first protect in countries where the laws are more clear, such as in Europe, and then enter other countries, including the U.S., when the rules are still being developed. Moreover, you can avoid countries where it does not seem that AI will be allowed at all and focus time and effort on those which could allow it. Overall, AI presents a lot of exciting opportunities in the field of life sciences and patenting technologies in this space presents some unique challenges. Until the rules surrounding patent eligibility become more clear, drafting AI-based applications with a focus on providing as much detail about the invention as possible, narrowing the claims to the invention, and looking for guidance from more established AI jurisdictions can improve the likelihood of of obtaining patent protection at home. Using Landscape, Patentability, and Freedom to Operate Studies to Guide Your Company's IP Strategy4/21/2020 We previously addressed the differences between landscape studies, patentability studies, and freedom to operate analyses so you should have a good understanding of what type of information will be gained from each. While there are some overlaps between the three types of studies, each study is meant to provide different information that can be used at different times to guide a company.

There are no one-size-fits-all rules for these studies as they can be utilized at various points to provide valuable information. In this post, we will examine how each type of analysis fits within a company’s overall business strategy in helping guide research, development, and ultimately, commercialization. Landscape studies Landscape studies form the foundation of a company’s business strategy. These studies are essentially a market analysis to help companies understand the existing technology and trends in a given technological area. Landscape studies will also identify the companies and inventors working in this technical area. Understanding the “state of the art” ultimately helps companies develop a plan for their technology. This plan can involve deciding to patent a particular invention, modify an existing one, or identify white space for further technological development. In addition, landscape studies can help identify possible collaborations that may require in- or out-licensing IP. Overall, a landscape study provides valuable information about the current market and its trends and allows companies to evaluate opportunities for developing new products, abandoning existing products, and exploring possible collaborations within the same space. Patentability studies Once an interesting idea is discovered, the next question is whether it can be patented. These ideas may be generated from landscape studies but often times they are simply generated in the course of research. Regardless of how they come up, patentability studies are designed to uncover prior art that could present hurdles to obtaining a patent. For instance, a patentability study, when done correctly, should identify both patent and non-patent literature which may interfere with an invention satisfying the standards of patentability, novelty (Section 102) and non-obviousness (Section 103). Understanding the prior that exists can help a company formulate a strategy for pursuing patent protection. This strategy may involve having to strengthening the support for the idea if there is complex prior art, modifying the idea if there is similar prior art, or simply presenting the idea as-is if no burdensome prior art is found. Often times a patentability study will reveal prior art that is in the same space. In these cases, knowledge of that prior art can help in drafting the patent application to include enough support to later overcome USPTO rejections related to that prior art. With the help of patentability studies, companies can better plan ways for satisfying the requirements of obtaining patent protection. Freedom to Operate Analysis Once the appropriate landscape studies and patentability studies have been conducted, and an idea is determined to be worthy of commercialization, the next question is whether there are any blocking patents that would prevent it from entering the market. This is done by a freedom to operate, or FTO, analysis. This type of analysis determines whether a product infringes another issued patent or may be encompassed by a pending patent application. It is done by identifying patents and patent applications that, if later issued as patents, may be infringed when commercializing your product. If a product or service is found not to infringe any third-party patents, then the product or service can generally be considered safe for commercialization. If, on the other hand, the product or service is found to infringe a third-party patent, then the company will have to explore possible ways of getting around that third-party IP. This can include designing around the third-party IP, licensing that IP, or challenging the validity of that third-party patent. Unlike landscape studies or patentability studies, FTOs should only be conducted when a product is already complete and ready for market. This allows its features to be analyzed against the claims of the third-party patent. Nevertheless, waiting too long to conduct an FTO may also be problematic as it could uncover block IP after significant time and expense has already been invested. Therefore, FTO’s should be conducted soon after a final version of the product is developed so that there is still time if changes need to be made or licensing discussions need to be explored. Conducting and understanding FTOs is an important step in helping a company identify possible hurdles to commercializing its product and to proactively develop a strategy for entering the market. Utilizing these three types of studies during the regular course of a business provides valuable information about the types of products and ideas already developed. Based on this information, companies can evaluate opportunities for developing, patenting, and commercializing new products. On March 30, 2020, the Honorable Miranda M. Du from the United States District Court for the District of Nevada ruled against Amarin and invalidated the company’s patents covering Vascepta® as being obvious. In doing so, Judge Du opened the door for Hikma and Dr. Reddy’s to launch generic versions of Vascepta®. In her ruling, however, Judge Du misconstrued the law of obviousness, in particular how secondary considerations are evaluated, and created an opportunity for Amarin to prevail on appeal. Here we will examine the law of secondary considerations and how it was misapplied.

In analyzing whether Amarin’s patents were obviousness, Judge Du held that the generics established a prima facie case of obviousness. In doing so, Judge Du held that a combination of prior art, namely Lovaza and Mori, rendered the claims obvious. A finding of obviousness, however, can still be overcome by focusing on the context for the inventive product rather than on the technical features of the invention. These arguments, which include i) unexpected benefits; (ii) satisfaction of long-felt need; (iii) skepticism; (iv) praise; and (v) commercial success are often referred to as “secondary considerations.” Generally speaking, showing any one of these could negate a finding of obviousness. In her review, Judge Du analyzed each of the secondary considerations and found that while long-felt need and commercial success weighed in favor of Amarin, the other factors weighed against it. At that point, Judge Du conducted a “weighing of the secondary considerations” and ultimately found that despite two factors (long-felt need and commercial success) supporting a finding on nonobviousness, those factors were outweighed by the secondary considerations which favored the generics. This is an unusual application of the law of secondary considerations and therefore a potential weakness in the Court’s holding that Amarin can exploit on appeal. The Court essentially weighed the secondary considerations against each other but the law of secondary considerations suggests they should be reviewed differently. An analysis of Section 103 obviousness stems from the Supreme Court case of Graham v. John Deere, 383 U.S. 1 (1966). Under Graham, Courts look at several factors when determining obviousness, including (1) the scope and content of the prior art, (2) the level of ordinary skill in the art, (3) the differences between the claimed invention and the prior art, and (4) objective evidence of nonobviousness. Of the four Graham factors, the issue of secondary considerations often creates confusion as many practitioners wonder how significant a role they play in an obviousness analysis. According to the Federal Circuit, however, secondary considerations are intended to play a role equal to or greater than the other Graham factors in an obviousness analysis: “It is jurisprudentially inappropriate to disregard any relevant evidence on any issue in any case, patent cases included. Thus evidence rising out of the so-called ‘secondary considerations’ must always when present be considered en route to a determination of obviousness…Indeed, evidence of secondary considerations may often be the most probative and cogent evidence in the record. It may often establish that an invention appearing to have been obvious in light of the prior art was not. It is to be considered as part of all the evidence, not just when the decisionmaker remains in doubt after reviewing the art (emphasis added).” In re Cyclobenzaprine Hydrochloride Extended-Release Capsule Patent Litigation, 676 F.3d 1063, 1076 (Fed. Cir. 2012). Based on this line of reasoning, secondary considerations should be weighed against the other three Graham factors, not against each other. Moreover, when weighed against the other three Graham factors, the secondary considerations should be given more weight. In fact, there are many instances where a secondary consideration, such as long-felt need, can overcome an obviousness challenge. In Eli Lilly & Co. v. Zenith Goldline Pharm., 471 F.3d 1369 (Fed. Cir. 2006), for example, the Federal Circuit affirmed the lower courts holding that a strong showing of secondary considerations, including information illustrating the long felt need to develop a safer and more effective antipsychotic medication olanzapine (Zyprexa®), was sufficient to overcome an obviousness challenge over a structurally similar compound, clozapine. In that case, testimony established that beginning at least 15 years prior to the discovery of olanzapine, a significant number of investigators were working to develop a safer and more effective antipsychotic drug because “[t]he medical need for better antipsychotic drugs in terms of increased efficacy and fewer unwanted effects is great.” In particular, it was established during trial that there was a need to find a replacement for clozapine due to the significant side effects experienced by patients, including movement disorders, bone marrow suppression and seizures. Moreover, even from the perspective of a patent prosecutor, most times we rely on only one or two secondary considerations when trying to overcome an obviousness rejection and thus we cannot and do not provide evidence of the others. This is due, in part, to the fact that the invention may not have yet generated information on certain secondary considerations. Commercial success and praise by others, for instance, may not apply to inventions that have not yet been commercialized. For these types of inventions, only long-felt need, failure of others, unexpected results, and skepticism of experts may be available. Moreover, there is not a certain number of secondary considerations that must be presented. It is up to the patent applicant or patentholder to provide the USPTO or court, respectively, with the secondary considerations that he feels are applicable and they should be reviewed on a case-by-case basis. In the Amarin case, Judge Du found that two secondary considerations weighed against invalidating the patents, and that by itself should have been sufficient to defeat the generics’ invalidity challenge. Now, this is not to say that any showing of secondary considerations should automatically overcome an obviousness challenge. If the prima facie case of obviousness is very strong, then a showing of secondary considerations may not be enough. In Pfizer, Inc. v. Apotex, Inc., 480 F.3d 1348, 1372, 82 USPQ2d 1321, 1339 (Fed. Cir. 2007), for instance, Court found that a strong case of obviousness could not be overcome by a showing that amlodipine besylate had allegedly unexpectedly superior results when compared to amlodipine maleate. While a strong showing of obviousness may outweigh a showing of secondary considerations, requiring the patentholder to present and defend every possible secondary consideration and then weighing them against one another is incorrect. As Amarin prepares its case for appeal, Amarin should gather caselaw holding that the Judge’s manner of weighing the secondary considerations against each other was inappropriate. Moreover, Amarin will likely show that the District Court’s application of the law was not a harmless application of the law, especially since weighing the secondary considerations against each other appears to have directly impacted the outcome of this case. If the Federal Circuit agrees that the application of the law of secondary considerations was erroneous, it is likely that the case will be remanded back to the District Court to correct its analysis and the dispute over Vascepta® may continue for another couple of year. The ongoing coronavirus pandemic highlights a potential conflict between patenting innovations by allowing companies to profit from their inventions and protecting public health by allowing people access to those treatments. This tension forms the basis of my first book, Intellectual Property and Health Technologies, and is also the overarching theme to my law school course.

As a result of the current outbreak, we are seeing many companies and universities devote significant resources to COVID-19 research in hopes of developing a vaccine or cure for the disease. The big question on many peoples’ minds: is what happens when someone develops a vaccine or cure? Will it be available to everyone? And at what cost will it be available? Last week I wrote about compulsory licensing and how countries can circumvent patents using that mechanism. We have already seen this with Israel announcing that AbbVie’s HIV treatment Kaletra® has been approved for importation despite the fact that patent protection for Kaletra® doesn’t expire until 2024 in Israel. In the U.S. there is also something called march-in right which allows the government to circumvent a patent and practice the invention itself or have a third party practice the invention. Below is a brief over of march-in rights in the U.S. and what they mean for the current pandemic. Overview of Bayh-Dole Act The Bayh-Dole Act, also called the University and Small Business Patent Procedures Act, is U.S. legislation that addresses intellectual property arising from federally-funded research. Enacted on December 12, 1980, the Bayh-Dole Act gives U.S. universities, small businesses and non-profit organizations the ability “to retain title to any invention developed under such support”. In other words, the Bayh-Dole Act allows U.S. universities, small businesses and non-profit organization to own the intellectual property that results from it rather than automatically vesting ownership rights in the government. Prior to the Bayh-Dole Act, inventions that arose out of federally funded research were owned by the government. The government, however, was not adept at commercializing the technology, and as a result, university technologies were not efficiently commercialized. Of the approximately 30,000 patents awarded to the government, for instance, only about five percent were licensed for use. According to Senator Bayh, “[d]iscoveries were lying there, gathering dust.” To stimulate innovation and promote the use and development of federally funded inventions, Senator Birch Bayh of Indiana and Senator Dole of Kansas sponsored the Bayh-Dole Act, which gave ownership of such technologies to the university. The thought behind granting ownership of the patented technology to the university rather than the government was that the university would be more efficient and successful at developing and commercializing the technology. The university would do this by entering into a license agreement with a company to grant access to the technology. In return for ownership of the technology, the university had to satisfy several requirements of Bayh-Dole, including: providing the government with a non-exclusive royalty-free license to the invention; patenting and commercializing the inventions; sharing a portion of any revenue received from licensing the invention with the inventor; providing licensing preferences for small businesses to facilitate the growth of small businesses; and requiring that the product be substantially manufactured in the U.S. Government’s March-in Rights A critical feature of the Bayh-Dole Act relates to the federal government’s right to maintain control over the technology that it funded. In what is known as the government’s right to “march-in,” the Bayh-Dole Act explicitly allows the government to step in and acquire technology under certain circumstances. Under this provision, the government, as the funding agency, has a right to “require the contractor [university], an assignee or exclusive licensee of a subject invention to grant a non-exclusive, partially exclusive, or exclusive license―in any field of use―to a responsible applicant or applicants, upon terms that are reasonable under the circumstances, and if the contractor, assignee, or exclusive licensee refuses such a request, to grant such a license itself.” In order words, the Bayh-Dole Act allows the government to ignore the exclusivity of a patent and practice the invention itself, or have a third party practice the invention on its behalf. The government’s rights, however, are not without limitation. To enforce its march-in rights, at least one of four criteria must be satisfied by the government, which include: (1) action is necessary because the contractor or assignee has not taken, or is not expected to take within a reasonable time, effective steps to achieve practical application of the subject invention in such field of use; (2) action is necessary to alleviate health or safety needs which are not reasonably satisfied by the contractor, assignee, or their licensees; (3) action is necessary to meet requirements for public use specified by Federal regulations and such requirements are not reasonably satisfied by the contractor, assignee, or licensees; or (4) action is necessary because the agreement required by section 204 has not been obtained or waived or because a licensee of the exclusive right to use or sell any subject invention in the United States is in breach of its agreement obtained pursuant to section 204. March-In Rights Case Studies The government has yet to exercise its march-in rights, making it difficult to determine exactly under what circumstances government intervention is likely. In the few petitions that were filed, however, it is clear that the most common scenario used to justify marching-in was the second criteria - to satisfy the "health and safety needs" of the public. Under this provision the petitioner claimed that the original licensor of the technology is inadequately addressing the public’s health and the government should therefore intervene allowing a third party to practice the technology. Anthrax Pandemic One scenario in which a petition for marching-in may be warranted is during an infectious disease outbreak, such as the current coronavirus pandemic. In 2001, for instance, the government contemplated invoking the march-in doctrine during the anthrax attacks following the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. At the time of the attacks, Bayer had patent rights to the drug Cipro®”, which was the most effective anthrax treatment at the time. It was unclear whether Bayer would be able to supply the required amount of drug needed to treat a potentially large population. As the anthrax scare continued and fear of a full-blown epidemic increased, the Department of Health and Human Services threatened to use the march-in rights to acquire Bayer’s patent rights to Cipro® and allow other companies to manufacture it. By allowing other companies to manufacture Cipro®, the government would ensure that enough drug supply would be available to the population. Ultimately, however, the government did not proceed with its petition. High Drug Pricing Apart from this one limited instance, march-in rights have surfaced mainly in connection with drug pricing. In the case involving Norvir® and Xalatan®, for instance, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) received a request to exercise march-in rights for patents covering Abbott Laboratories’ HIV/AIDS drug, Norvir®, and Pfizer's glaucoma drug, Xalatan®, arguing that both drugs were priced too high. While Abbott increased the price of Norvir® 400% for U.S. consumers but not for other countries and Xalatan® was sold in the U.S. at up to five times the cost compared to other high-income countries, the NIH denied both petitions. In doing so, the NIH cited the availability of the drugs and also the lack of evidence suggesting that the health and safety needs of the public were not being adequately met by the companies. Moreover, the NIH considered the topic of drug pricing to be outside its jurisdiction and one that should be addressed by Congress. Drug Shortage In 2010, the NIH was petitioned to exercise its rights in response to a drug shortage. The petition asked the NIH to review Genzyme's inability to manufacture enough Fabrazyme® to treat Fabry patients as a result of manufacturing problems and FDA sanctions. To alleviate the drug shortage, petitioners asked the NIH to allow other manufactures to begin supplying the proper drug. The NIH again denied the march-in petition, but unlike in the previous situations, the government believed that marching-in in this situation would be futile given the length of time required to bring a generic version, or biosimilar, of Fabrazyme® to market. Because of the uncertain FDA approval process, the NIH contended that the drug shortage would not be solved any faster even if other companies were given the opportunity to manufacture the drug. Implications for Current Pandemic While the U.S. government has yet to exercise its march-in rights, the current pandemic could provide its first opportunity to do so. Companies that are working to develop COVID-19 treatments, including Moderna and Gilead Sciences, have each benefited from government funding. Remdesivir®, Gilead Sciences’ antiviral that has shown promise in treating COVID-19, was developed at the University of Alabama at Birmingham and has received approximately $38 million from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The NIH itself has spent around $700 million to develop a vaccine to coronavirus. The implications of this are potentially huge because it sets up the U.S government to circumvent any patents that could stand in the way of getting treatment to the public. Even though the U.S. government has yet to exercise its march-in rights, companies developing products with the aid of government funding are subject to Bayh-Dole and the march-in rights. This, however, does not mean that the government will necessarily have to exercise its power. For instance, there could potential logistical problems with doing so. Some drugs, particularly biologic ones, are often challenging to manufacture. They require very specific materials and processes to be used to yield the correct product so asking a different company to manufacture a biologic drug could result in a significantly different end product. At best, this end product would not be effective at treating the disease, and at worst, it could cause harm. Moreover, there is no evidence to say that drug companies will not make their drug available and accessible to all. We have already seen AbbVie give up its patent rights to Kaletra® in an effort to fight the pandemic. Other companies will likely follow suit considering the public relations nightmare they may otherwise face. As I have mentioned before, protecting innovation and protecting the public’s health do not have to be mutually exclusive concepts. Allowing a company to make a profit from their drug and fund future innovation does not mean that people should be denied access to the drug, especially in the case of a pandemic. These two concepts can work together to bring newer and better treatments to the market and at the same time make people healthier. As I have mentioned before, patent rights are not absolute, but neither is the right to circumvent those rights. In a time when restoring global public health is at an all-time high, patent rights and public health rights must work together to not only develop new treatments, but also to rid the public of COVID-19. IP Considerations When Patenting Pre-Existing Technologies Surrounding COVID-19 and Other Diseases4/8/2020 When deciding what product to pursue and patent, companies generally have two options: start from scratch and develop a truly novel product or find one that has already been around and repurpose it for another use. Repurposing technologies can offer viable opportunities for companies looking to expand their product portfolios since working with pre-existing technologies eliminates many of the hurdles associated with developing de novo products. This is especially true of therapeutics since the discovery of effective, safe therapeutics remains costly, time-consuming, and risky.

We are seeing this dynamic unfold in the current COVID-19 pandemic. Companies and universities are working to see if existing pharmaceuticals, vaccines, treatments, and diagnostics can be used to fight against the novel virus. Several U.S. companies have already announced that their research into COVID-19 has resulted in the filling of patent applications covering coronavirus treatment. For instance, Texas-based Moleculin Biotech took their existing inhibitor compound WP1122 and tested it to see if it could limit coronavirus replication by depriving the host cells of energy. There are two main hurdles when it comes to IP issues involving a pre-existing technology: novelty under 35 U.S.C. Section 102 (“Section 102”) and obviousness under 35 U.S.C. Section 103 (“Section 103”). We will address these in turn. Section 102: Novelty One of the main hurdles to overcome when patenting a pre-existing technology is novelty, or Section 102. As applied to a pre-existing drug, Section 102 requires that it not be previously patented, described in a printed publication, in public use, on sale, or otherwise available to the public before the patent application is filed. In other words, a claim to the pre-existing technology must recite something not previously known to the public. For drug patents, most composition of matter claims reciting only the pre-existing drug will run afoul of Section 102 because the drug was previously known to the public, and thus, would be considered prior art to any subsequent patent application. Accordingly, composition claims including pre-existing drugs need to include new elements not anticipated by the earlier disclosure. Below are ways to overcome Section 102 hurdles to obtain claims directed to previously-known technologies. Reciting new uses One way to obtain claims directed to previously-known technologies that overcome a Section 102 challenge is to draft claims reciting a novel use for that technology, such as a new indication in the case of a drug. If the original claims were directed to a cancer indication, for instance, a novel use would be to claim a cardiovascular indication. We are seeing this play out with existing drugs, such as AbbVie’s HIV drug, Kaletra®, being tested on COVID-19 patients. Such method claims are often difficult for competitors to design around, and they are also available in many foreign jurisdictions, although they may be drafted in slightly different formats. Other uses could include new dosage amounts, different formulations, better safety, better tolerability, new way of administration, and so forth. Recite new dosage forms For drugs, specifically, another way to claim a previously-known drug is to claim novel pharmaceutical dosage forms. Pharmaceutical dosage forms can be, for example, gels, solids, liquids, or sustained or extended-release forms. Other examples of dosage forms can be for a specific type of administration including oral, parenteral, intramuscular, and the like. Many variations of pharmaceutical dosage forms are available and lend themselves to drafting novel claims that overcome Section 102 rejections. Develop new combinations A final approach for overcoming a Section 102 hurdle is to combine two pre-existing technologies into one product. In the case of drugs, one can incorporate the pre-existing drug into a composition including one or more other compounds to form a novel combination. For instance, Pfizer’s drug, Caduet®, is the combination of the calcium channel blocker, Norvasc®, and the cholesterol-lowering agent, Lipitor®, which expired in 2007 and 2011, respectively. As a side note, combining more than one product into one overall product can have the added benefit of extending the patent term. Caduet®, for instance, expired in 2018 which is about seven years after the last expiration of one of their products. To overcome novelty objections with combination products, applicants should be prepared to focus on new uses of their products and to draft their patent applications with sufficient disclosure to address these new uses. Such combination claims should include additional features, such as specific drug amounts or ratios between the drugs to increase their likelihood of being found patentable over what was previously known in the prior art. Nevertheless, combinations of one or more products can be patentable. While the repurposed technology can be any new use, new form, or even new combination that is novel for the purpose of overcoming Section 102, such modifications to the pre-existing technology may nevertheless encounter Section 103 obviousness hurdles as the modification may be obvious to one skilled in the art. Below we explore Section 103 and provide suggestions for overcoming rejections to pre-existing technologies. Section 103: Obviousness Obviousness rejections under Section 103 for pre-existing technologies can be based on a combination of several prior art references, each of them teaching one or more aspects of the rejected claims. Overcoming an obviousness rejection can, therefore, be complex. Overcoming obviousness rejections often turns on arguments that focus on the context for the inventive process rather than on the technical features of an invention. These arguments, which include the invention’s commercial success, satisfying a long felt but unsolved needs, failure of others where the invention succeeds, and the appearance of unexpected results are often referred to as “secondary considerations.” The most effective way of overcoming obviousness rejections employing these secondary considerations requires early planning and foresight. Before the patent application directed to the new use of the pre-existing technology is drafted and filed, one should think about possible obviousness rejections the application might face and, when possible, design and conduct experiments to generate data that will help overcome these rejections. Commercial success Showing commercial success of an invention is one way of overcoming an obviousness rejection. In theory, if a product that is commercially successful was obvious to invent, then competitors likely would have already developed it. Therefore, if a product is commercially successful, one argument in overcoming obviousness is that others also recognized the product’s potential for commercial success but failed in their commercial attempts to develop a solution to the same problem. Including information showing a connection between the novel aspects of the patent claim(s) and the commercial success is often required in demonstrating non-obviousness based on commercial success. Discussing complex hurdles Another possible argument against obviousness is disclosing a prior, unappreciated problem or complex hurdle the inventors overcame in a non-obvious manner. In this situation, the inventors could point to wide-spread skepticism that a hurdle could not be overcome using known methodologies. Showing that the methodology for overcoming the hurdle or problem was unique can be a successful strategy when overcoming an obviousness challenge. Failure of others Yet another possible argument in overcoming an obviousness rejection is to show that previous studies either failed at developing the claimed invention or indicated the claimed invention would not work. In this situation, it is necessary to have a clear understanding of research in the space and point to any shortcomings. Including such shortcomings in a patent application can greatly help overcome obviousness rejections down the road. Unexpected results Another strong argument in overcoming an obviousness rejection is by showing unexpected results. This can include data showing that the pre-existing drug has a surprising effect—that it works at the higher/lower dose used, that a combination of drugs demonstrates synergy when used together, or that it has a different mechanism of action for a new use—that would not have been expected based on what was known at the time. Such examples of unexpected results can greatly help to overcome obviousness rejections, and as such, designing experiments to help generate this data is important. If the experiments to generate the above argument are not planned before the application is drafted and filed, they could still be conducted while the application is being prosecuted. Some countries, including the U.S., allow post-filing data to be submitted during prosecution. Post-filing data is that which is generated after the application is filed and thus not part of the originally-submitted application. Generating post-filing data is often worthwhile, especially when you cannot predict the kind of experiments or data that will be necessary to overcome a rejection. Overall, overcoming novelty and obviousness rejections for repurposed technologies is not only possible, it can also offer a faster and more efficient way of bringing potentially valuable products to the market. To successfully obtain patent protection to the new product, be prepared to provide a lot of information. The more information you have about how the repurposed product was generated and how it differs from the previously-known versions, the better the chances are of overcoming possible rejections. |

Welcome!BioPharma Law Blog posts updates and analyses on IP topics, FDA regulatory issues, emerging legal developments, and other news in the constantly evolving world of biotech, pharma, and medical devices. Archives

March 2021

Categories

All

|

Practices |

Company

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed